Light, optics and perception; these are the elements that occupy artist Daniel Soder. His color-filled abstract photographs and exquisitely crafted geometric sculptures only hint at the scientific inquiry that lies at the heart of his practice. Through multi-stage experiments, his works explore how light reacts to different surfaces and how the human eye perceives these interactions.

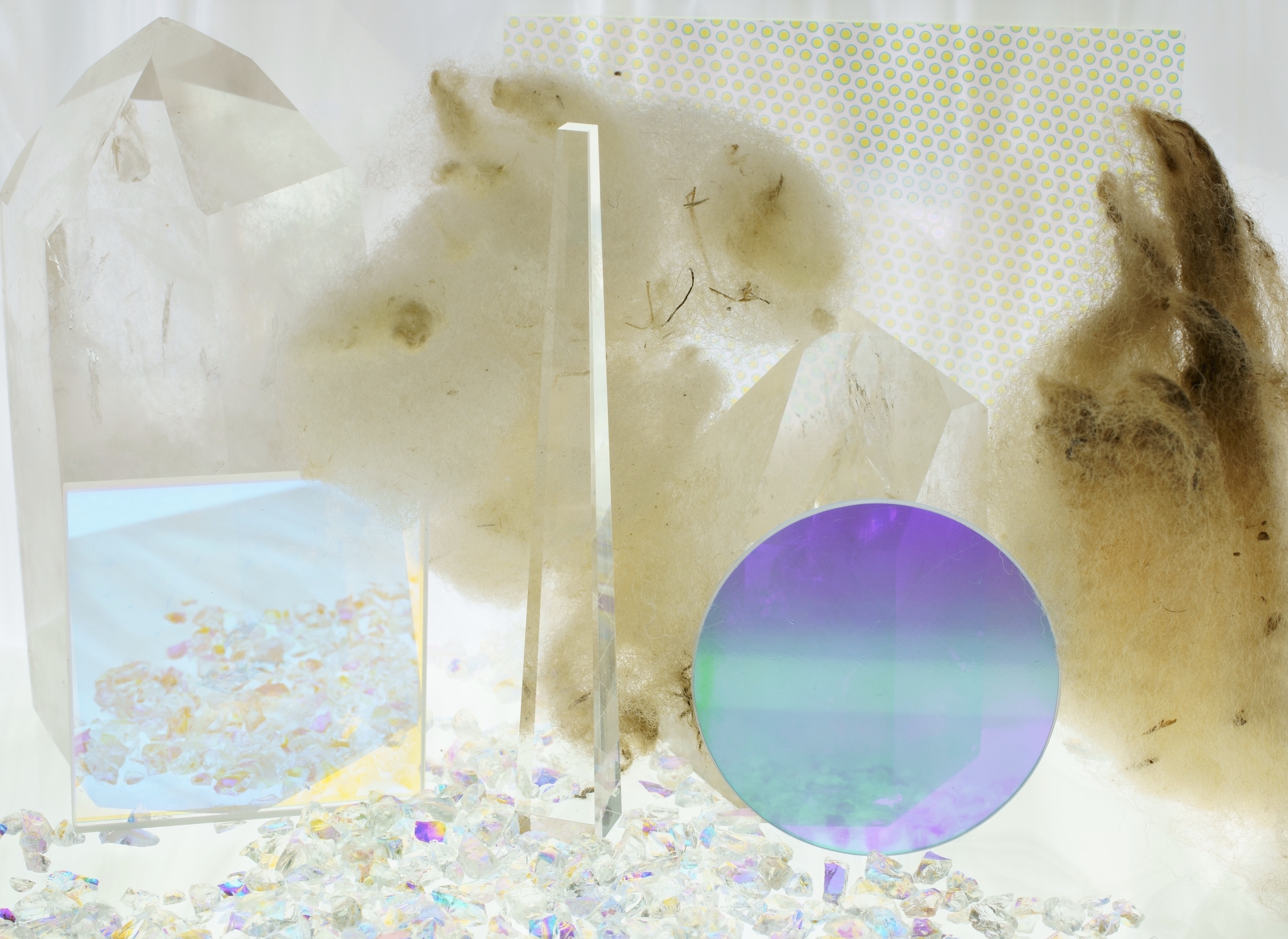

For Soder, the camera is a mechanism for capturing light rather than for representing life. His photographs begin as tabletop vignettes that the artist builds in a black-box studio from an array of crystals, prisms, mirrors, and glass. As he directs different light sources at and through the objects, he captures the effects on film. Because the camera actually perceives things differently than the naked eye, he shoots with his digital camera tethered to a screen so he can see what the lens sees. This allows him to tweak the composition and lighting until he finds the image he is looking for.

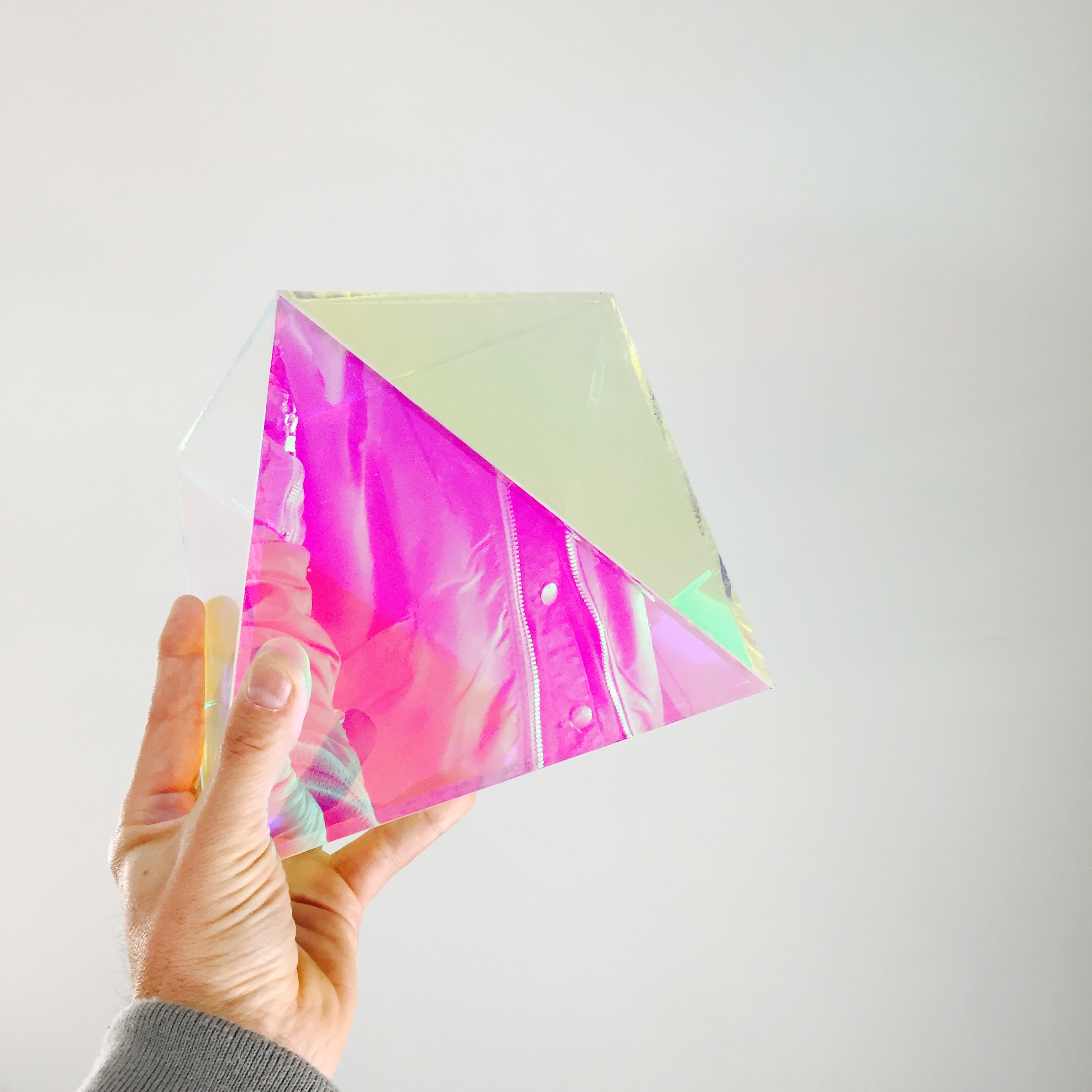

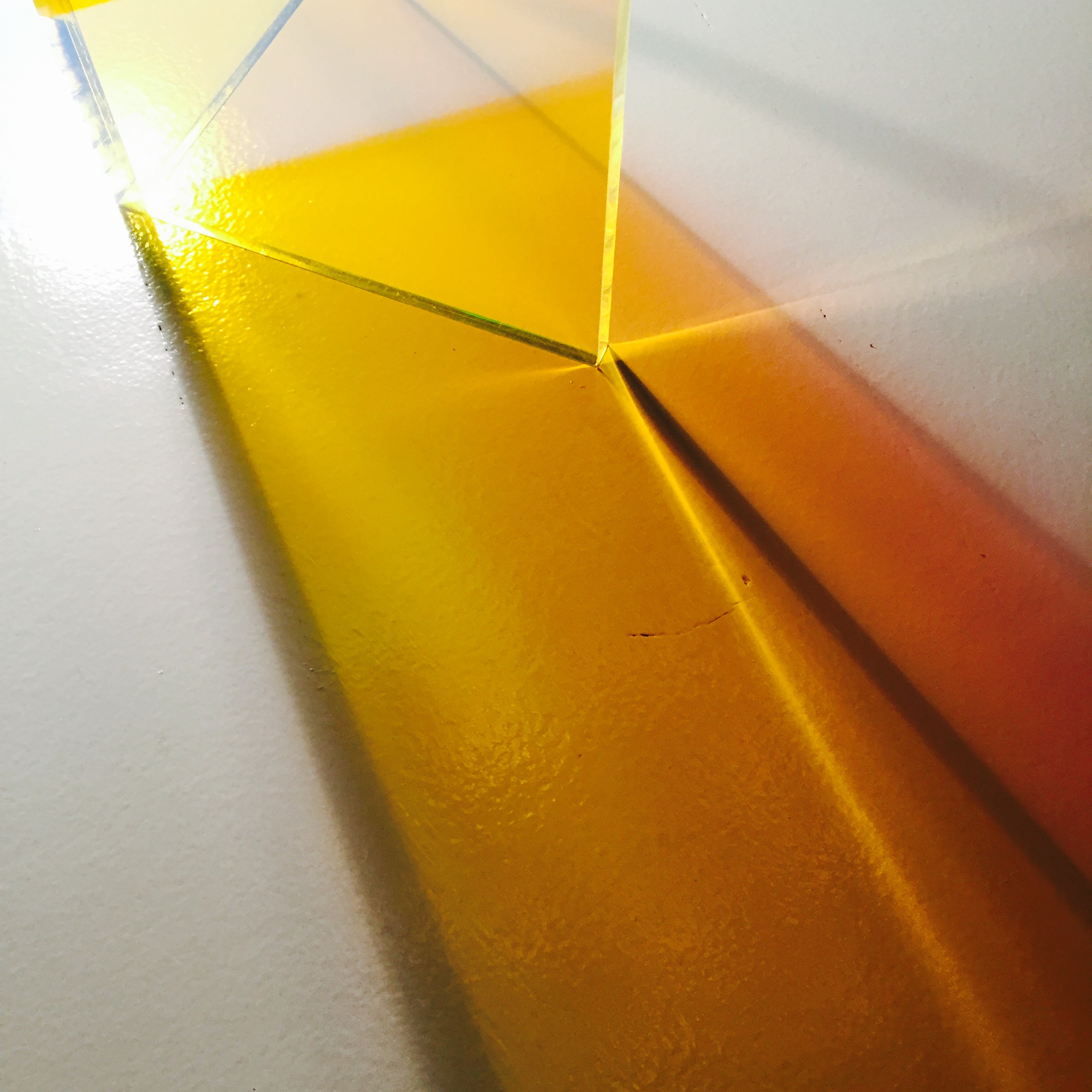

His sculptures also evolve from a multi-step process. They evolve from three-dimensional cardboard maquettes whose shape mimics crystalline structures that exist at a sub-atomic level. He then translates these geometric variations into cube-like sculptures, replacing the cardboard with an array of transparent, translucent and reflective materials.

Light passing through and bouncing off the various planes challenges our notions of color, volume and scale.

The California Light and Space artists like James Turrell, Larry Bell, and Mary Corse, are a clear inspiration for Soder. Their explorations, which began in the 1970’s, focus on the viewer’s experience of light and other sensory phenomena. His methodology, however, is more akin to younger artists like Sara van der Beeck, Eileen Quinlan, and Jessica Eaton, whose compositions are created by the manipulation of light, color and exposure in highly controlled environments.

While Soder studied photography in college, the origins of his curiosity may have come much earlier. His father was a prominent radiologist in Atlanta and Soder recalls sitting on his father’s lap as he read X-rays, MRIs and CT scans. While the young Soder most likely did not grasp the complexity of how rays passing through the body can be captured on film and used to create both two dimensional and three-dimensional images, he did understand the importance of an interface being used to represent something we cannot readily see.

While Soder studied photography in college, the origins of his curiosity may have come much earlier. His father was a prominent radiologist in Atlanta and Soder recalls sitting on his father’s lap as he read X-rays, MRIs and CT scans. While the young Soder most likely did not grasp the complexity of how rays passing through the body can be captured on film and used to create both two dimensional and three-dimensional images, he did understand the importance of an interface being used to represent something we cannot readily see.

After college, Soder found his way into advertising, where he developed an expertise introducing new brands into the Asian market. His job was to make people want things, to manipulate their perception, and this preoccupation continues in his artwork. The difference is in the removal of images: Soder’s photographs and sculptures provide a purposeful respite from our picture-laden society and focus our attention on the wonder of our observations.

There is so much around us that exists independently of whether we can see it. Soder’s photographs and sculptures are a reminder of our optical limitations and an invitation to experience a non-mediated sense of awe in its purest form. They ask us to explore and to enjoy the rareness of the world in which we live.

There is so much around us that exists independently of whether we can see it. Soder’s photographs and sculptures are a reminder of our optical limitations and an invitation to experience a non-mediated sense of awe in its purest form. They ask us to explore and to enjoy the rareness of the world in which we live.